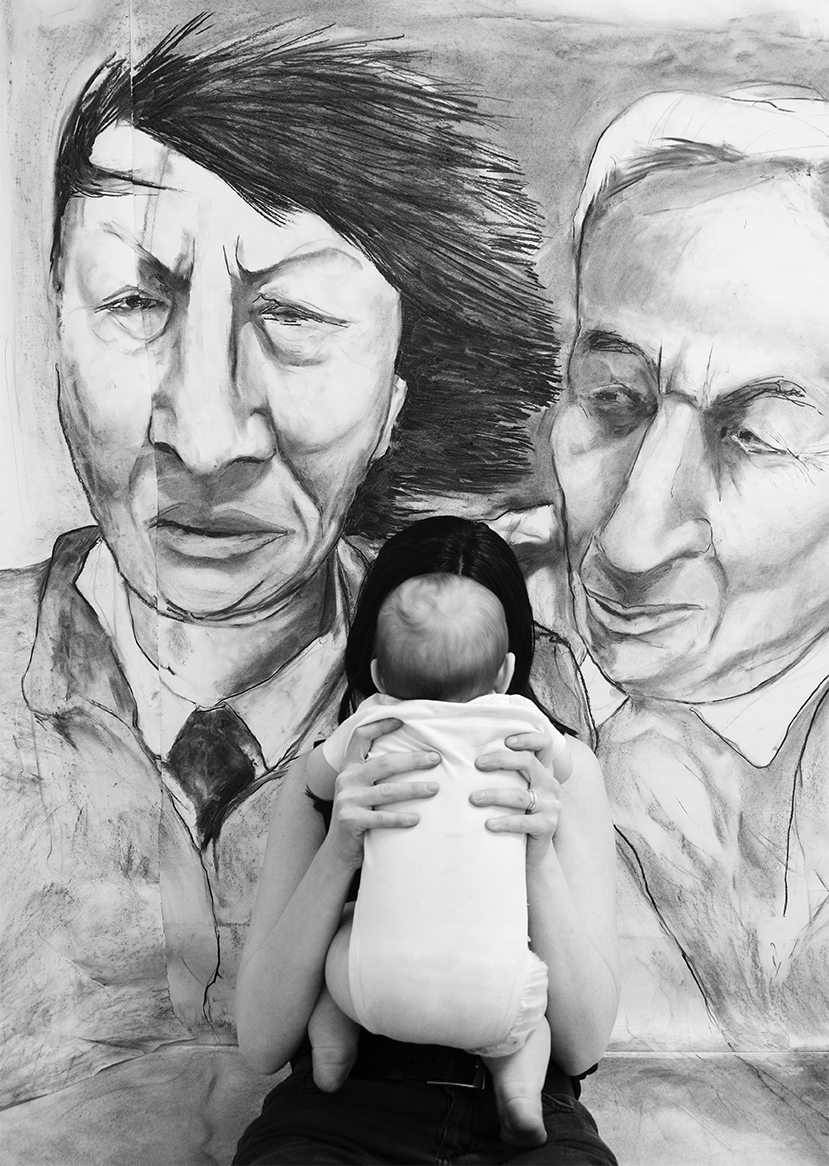

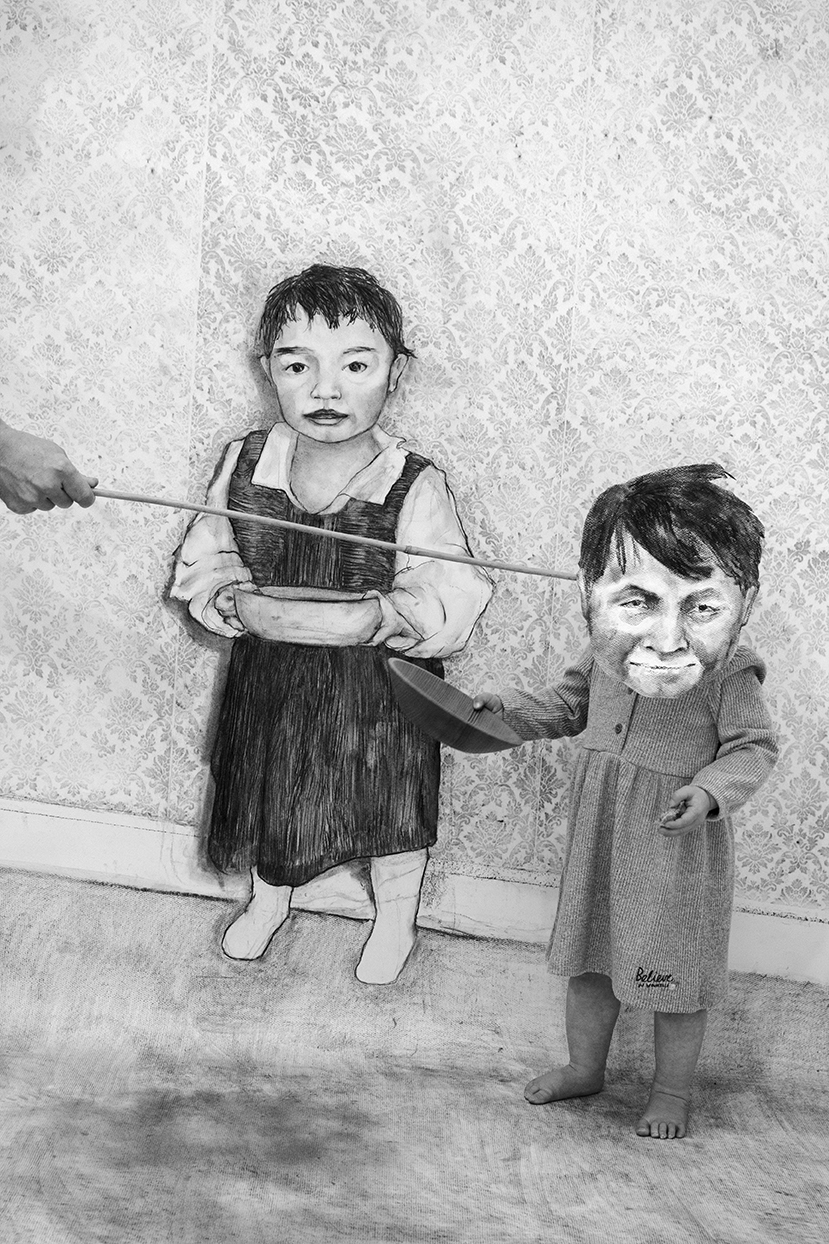

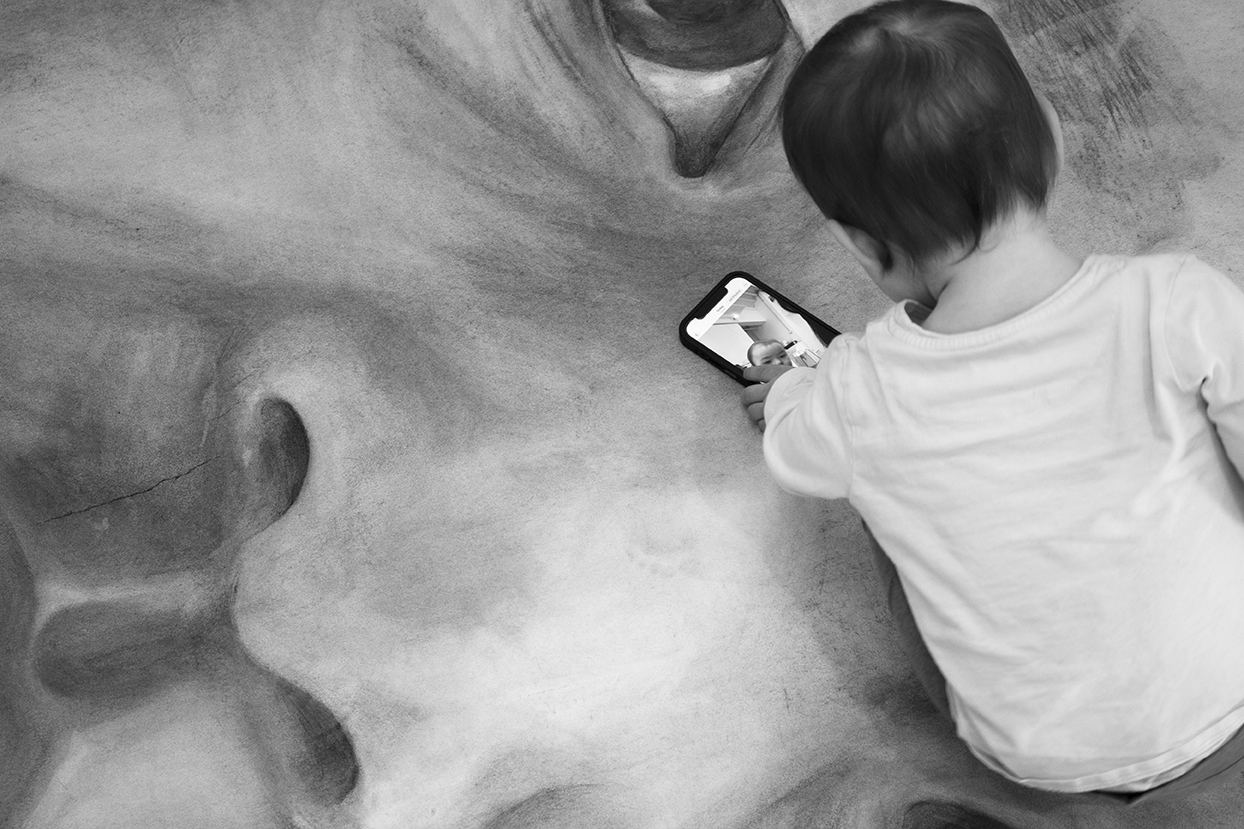

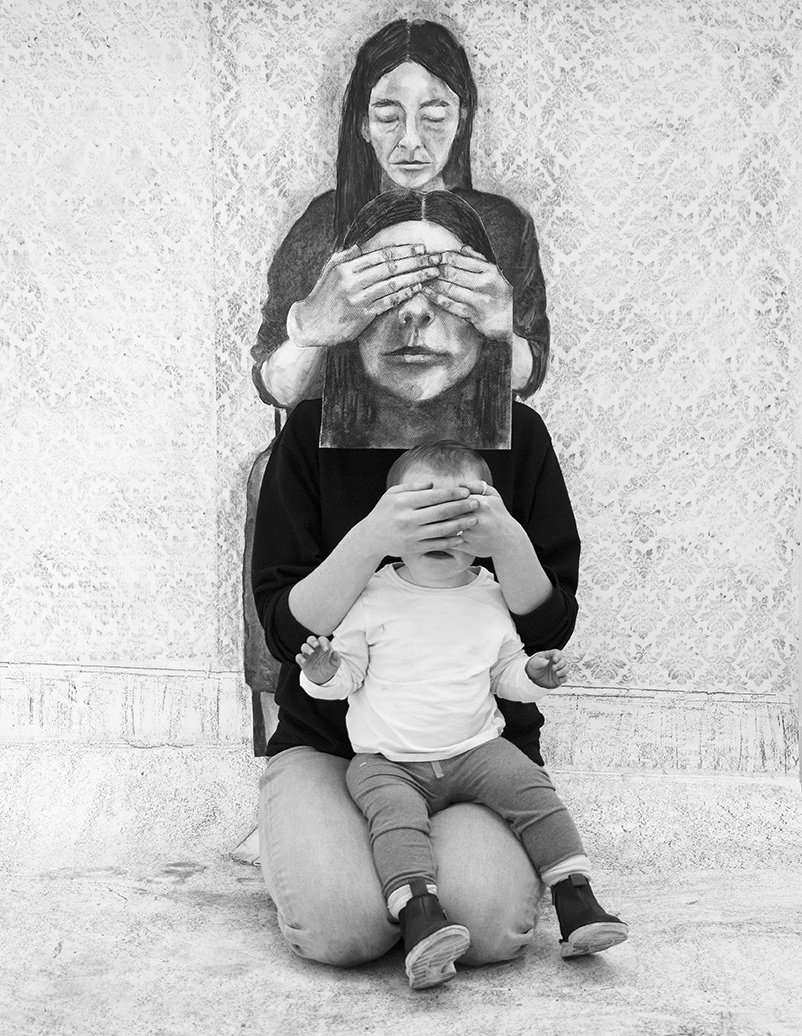

Unwilling Collaborator

2025 - ongoing

2025 - ongoing

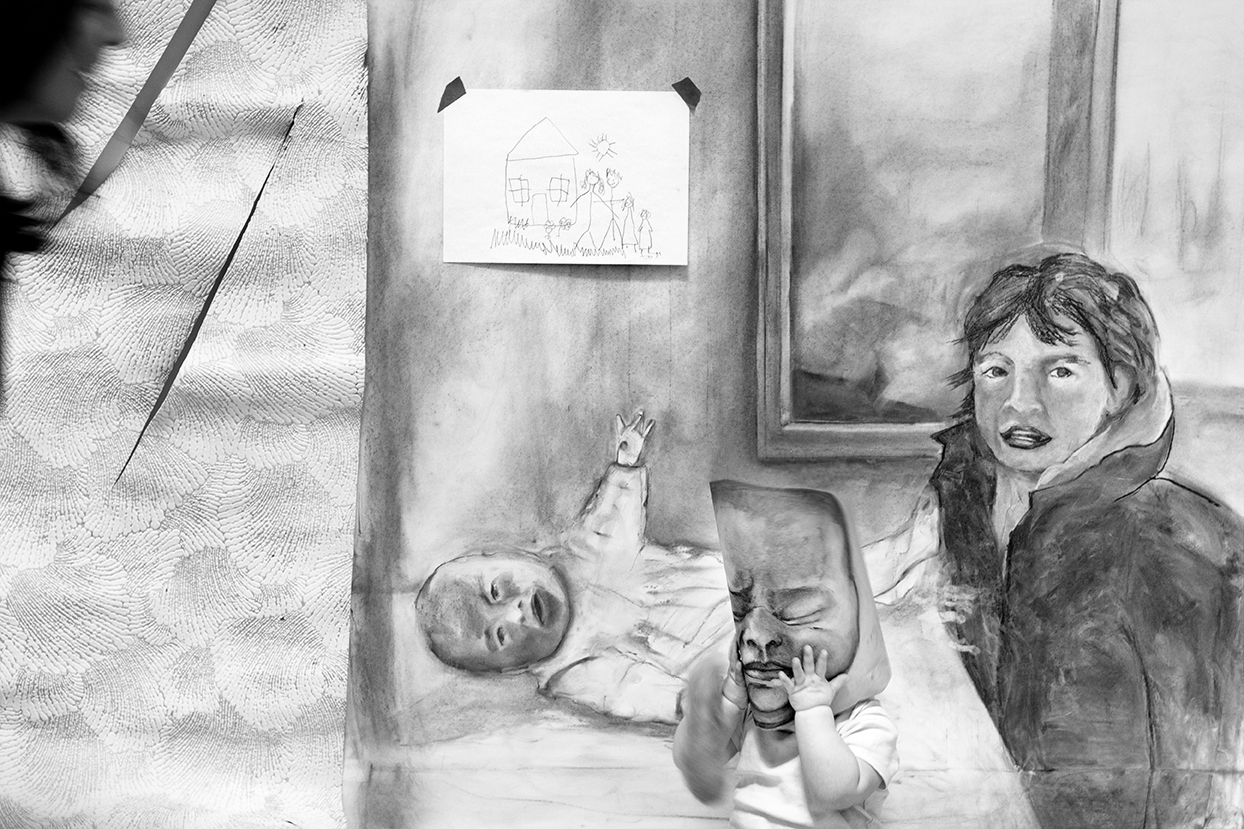

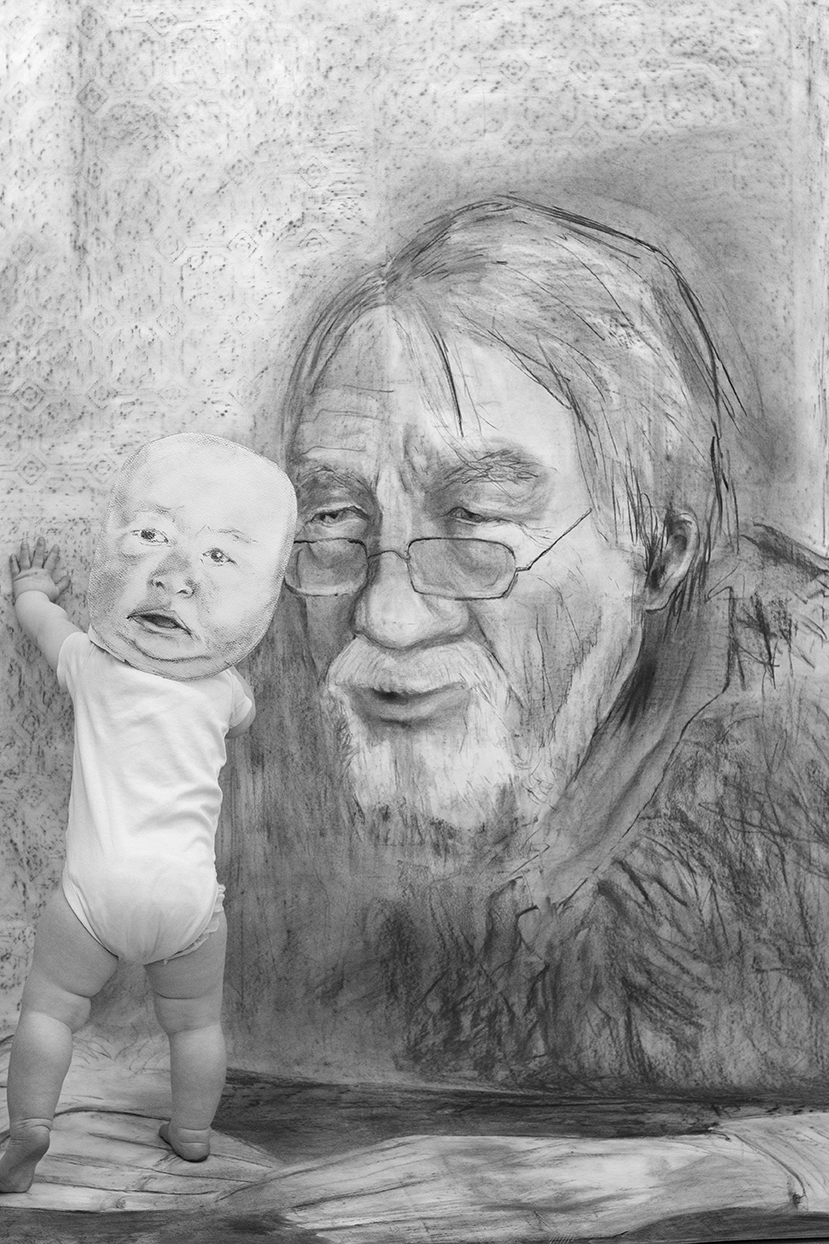

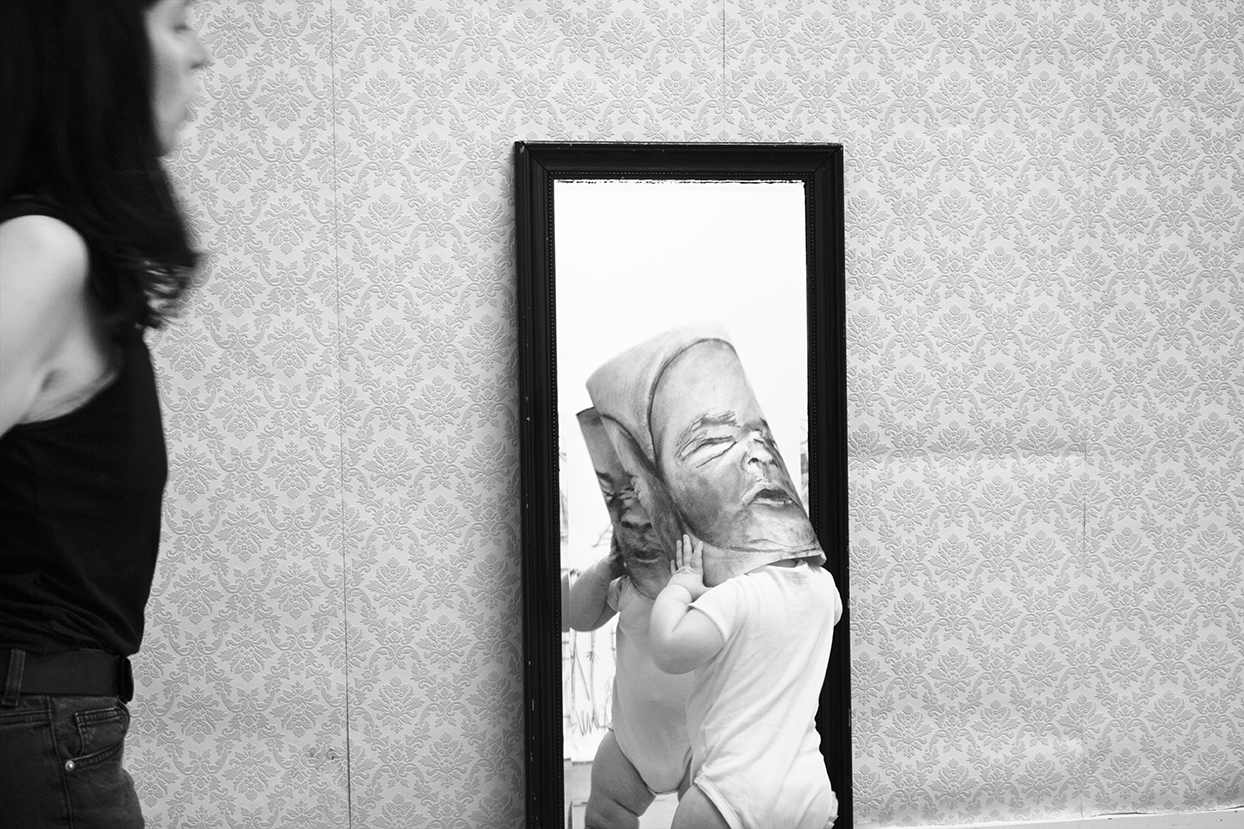

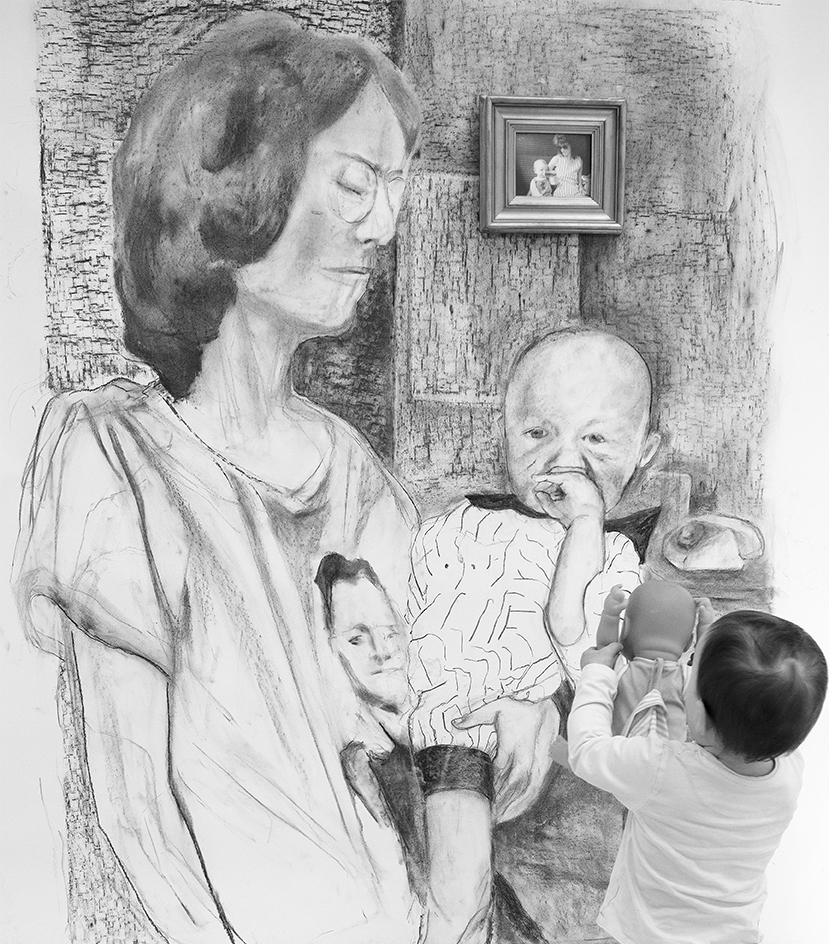

Unwilling Collaborator is a collaboration with my one-year-old daughter exploring how the families we create are haunted by the families we come from. At a time of increased photo sharing on social media and powerful online facial recognition technology, my project also reflects on the overlapping imagery represented by faces, masks and screens.

Like many new parents, I am interested in – and fearful about – how my own childhood experience will shape my relationship with my daughter. This photo series, both as process and in the resulting images, is intended to provoke thinking about boundaries, storytelling, honesty and control. As well as exploring a mother/daughter relationship, the photographs stage the issue of how a parent chooses to frame and document their child.

Works in progress at Artwalk Porty

14-15 September 2024

14-15 September 2024

Leith School of Art, Edinburgh

15 September - 14 December 2023

This exhibition of ceramics and accompanying works explores the materiality of domestic space – the walls, wallpaper, and personal paraphernalia that are the stuff of our immediate surroundings at home.

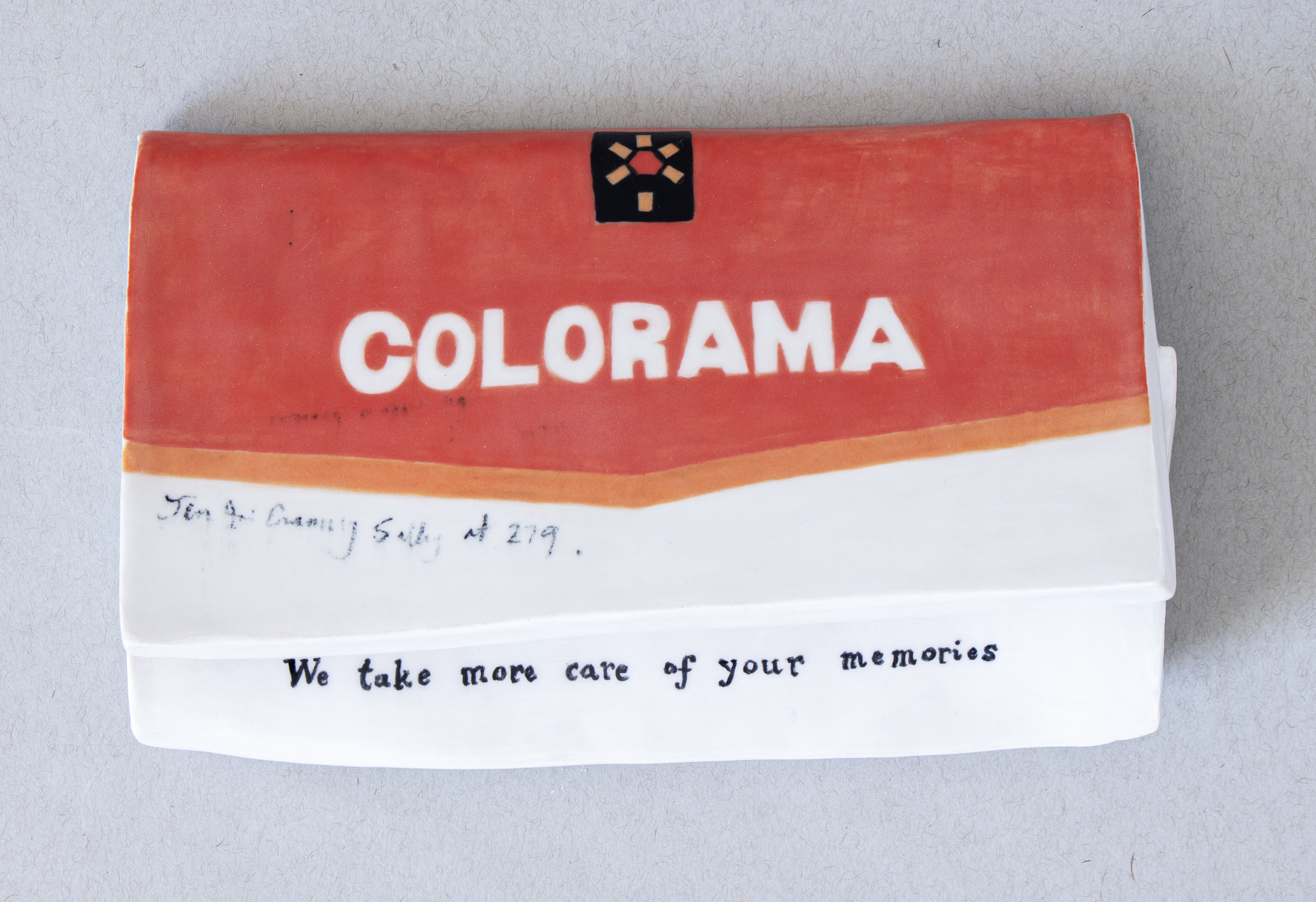

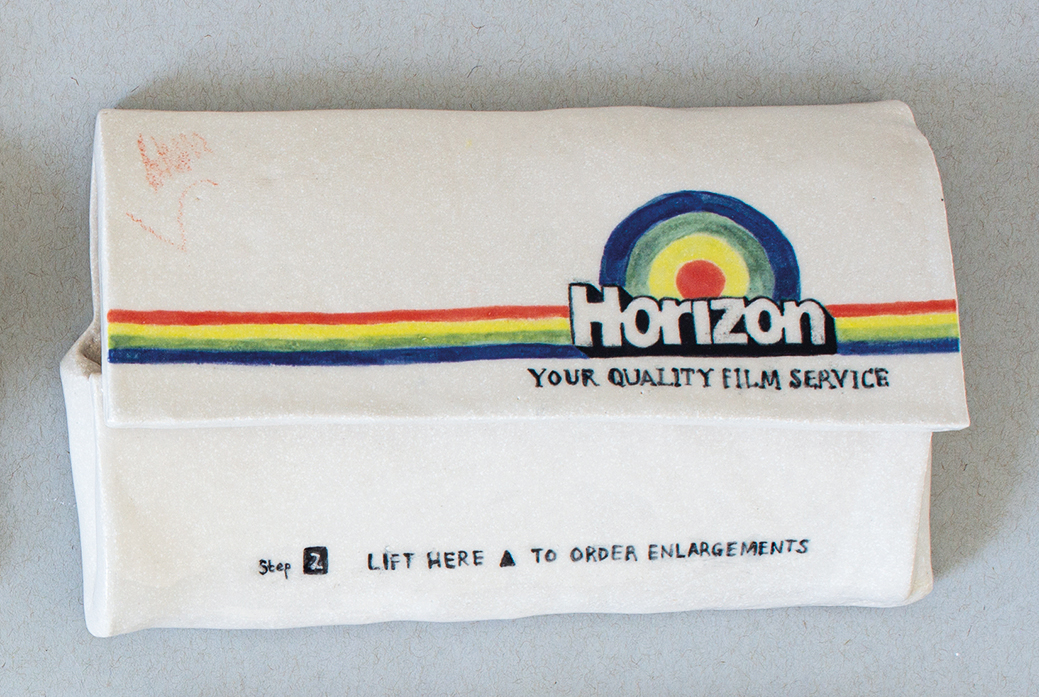

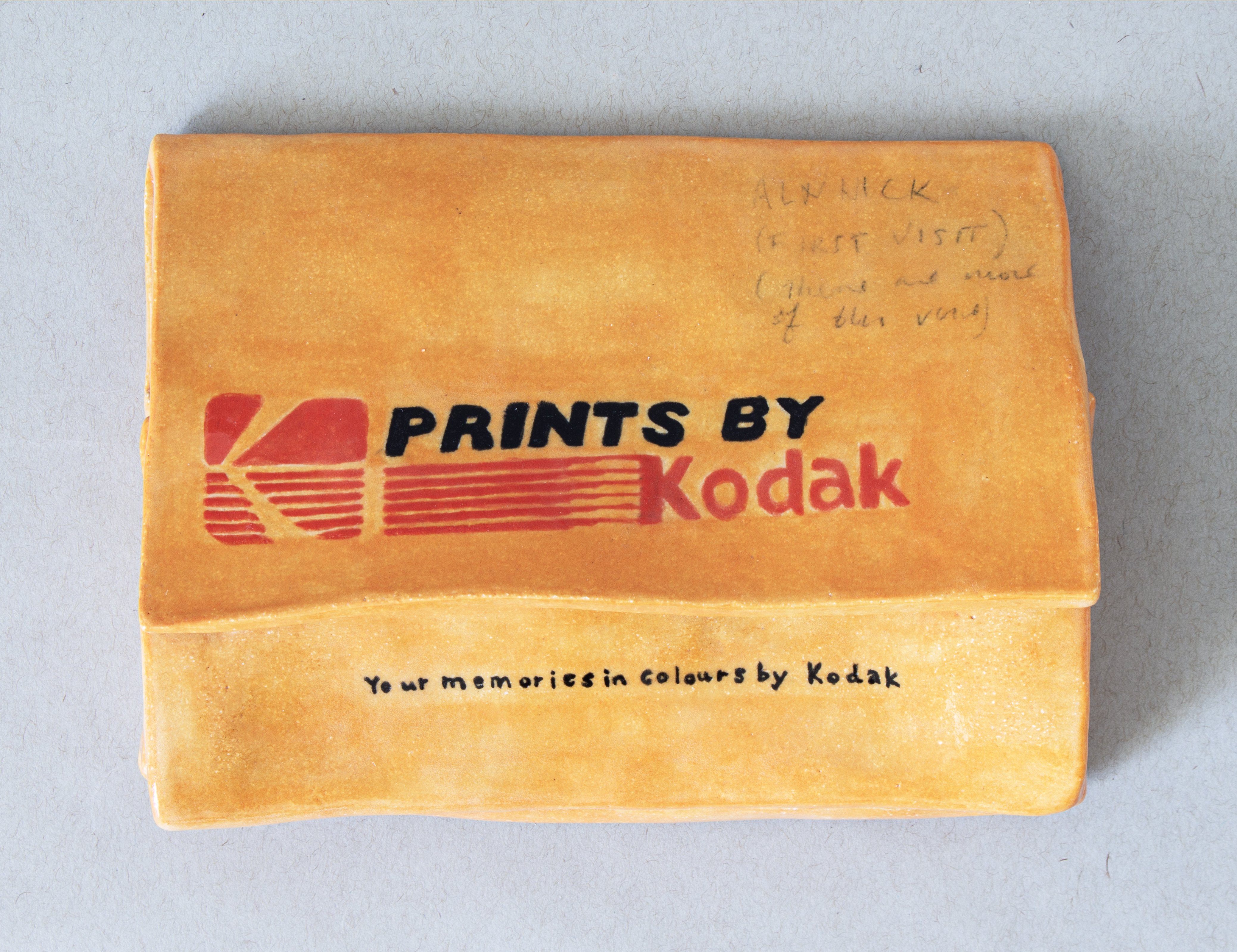

The works invite reflection on how we write ourselves into the spaces we live in and why we keep the things we keep: the hundreds of photos of nameless views; the albums collected from the chemist still in their original packaging; the children’s drawings that make it onto the kitchen wall and stay there.

The starting point for Slow Edit was a stack of 90s paper photo albums from the artist’s childhood and the textured wallpaper that covers her studio walls. With digital technology increasingly replacing the paper trails of lives lived, the works explore how our memories are embedded in the materials around us and within the material culture of our times.

Quick Photo series

2023

Glazed stoneware

Left:

Fingers

2023

Stoneware with glaze

9x 28cm

Fingers

2023

Stoneware with glaze

9x 28cm

Right:

Siblings

2023

Stoneware with glaze

28 x 28cm

Siblings

2023

Stoneware with glaze

28 x 28cm

House piece (i-iii)

2023

Glazed stoneware with acrylic and varnish

Each 24 x 24cm

Crack

2023

Stoneware with glaze, acrylic and varnish

28 x 38cm

Wrinkle

2022

Glazed stoneware

18 x 24cm

Kitchen Wall

2023

Stoneware with glaze, acrylic and varnish

20 x 30cm

Worn (i)

2023

Stoneware

30 x 30 x 12cm

Worn (ii)

2023

Stoneware

30 x 30 x 12cm

Left:

Flaking

2023

Stoneware with glaze

30 x 37cm

![]()

Flaking

2023

Stoneware with glaze

30 x 37cm

Right:

Pattern

2023

Plaster

40 x 55cm

![]()

Pattern

2023

Plaster

40 x 55cm

2023

Assorted fabrics

90 x 210cm

Verdant Works, Dundee

5 August - 26 November 2023

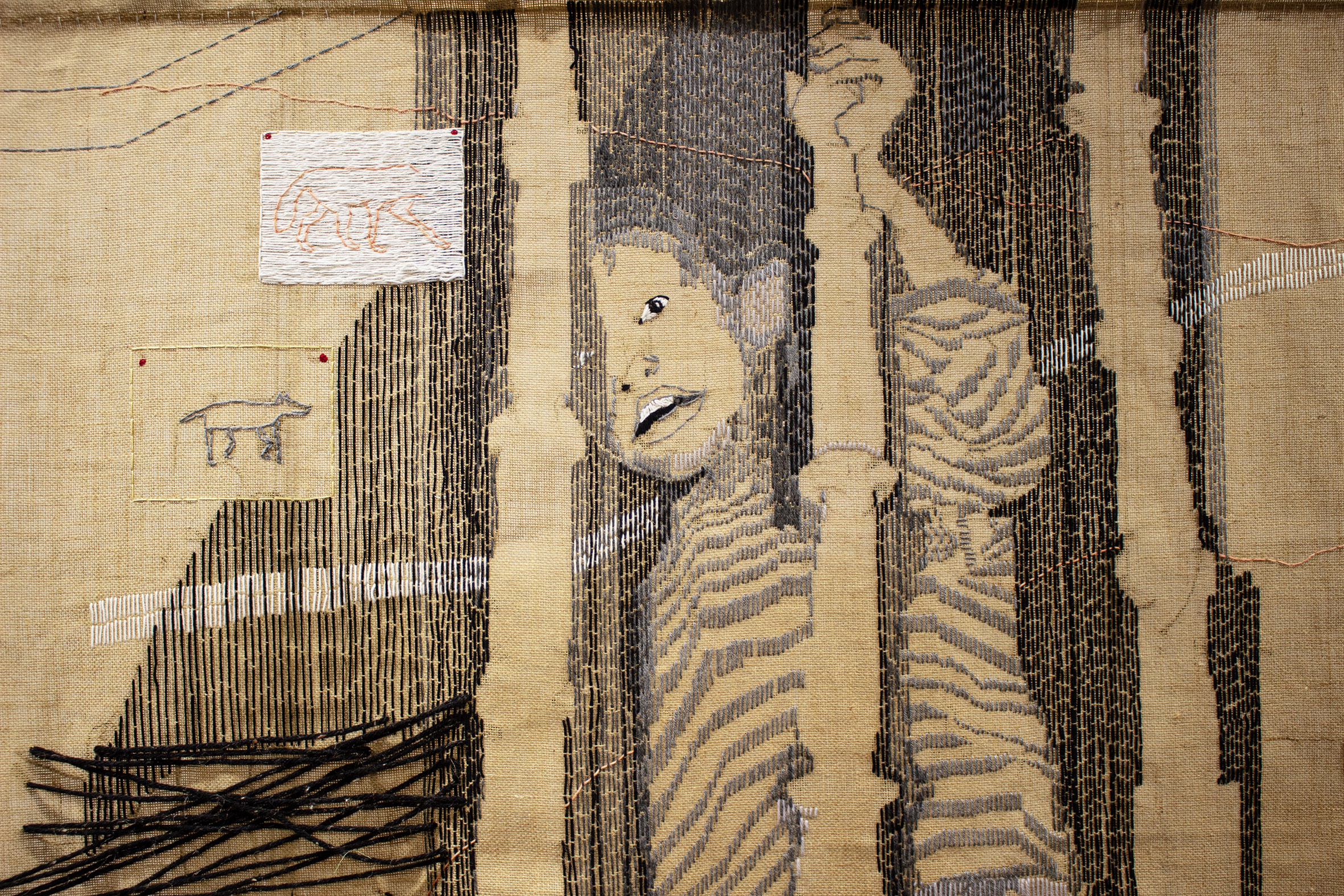

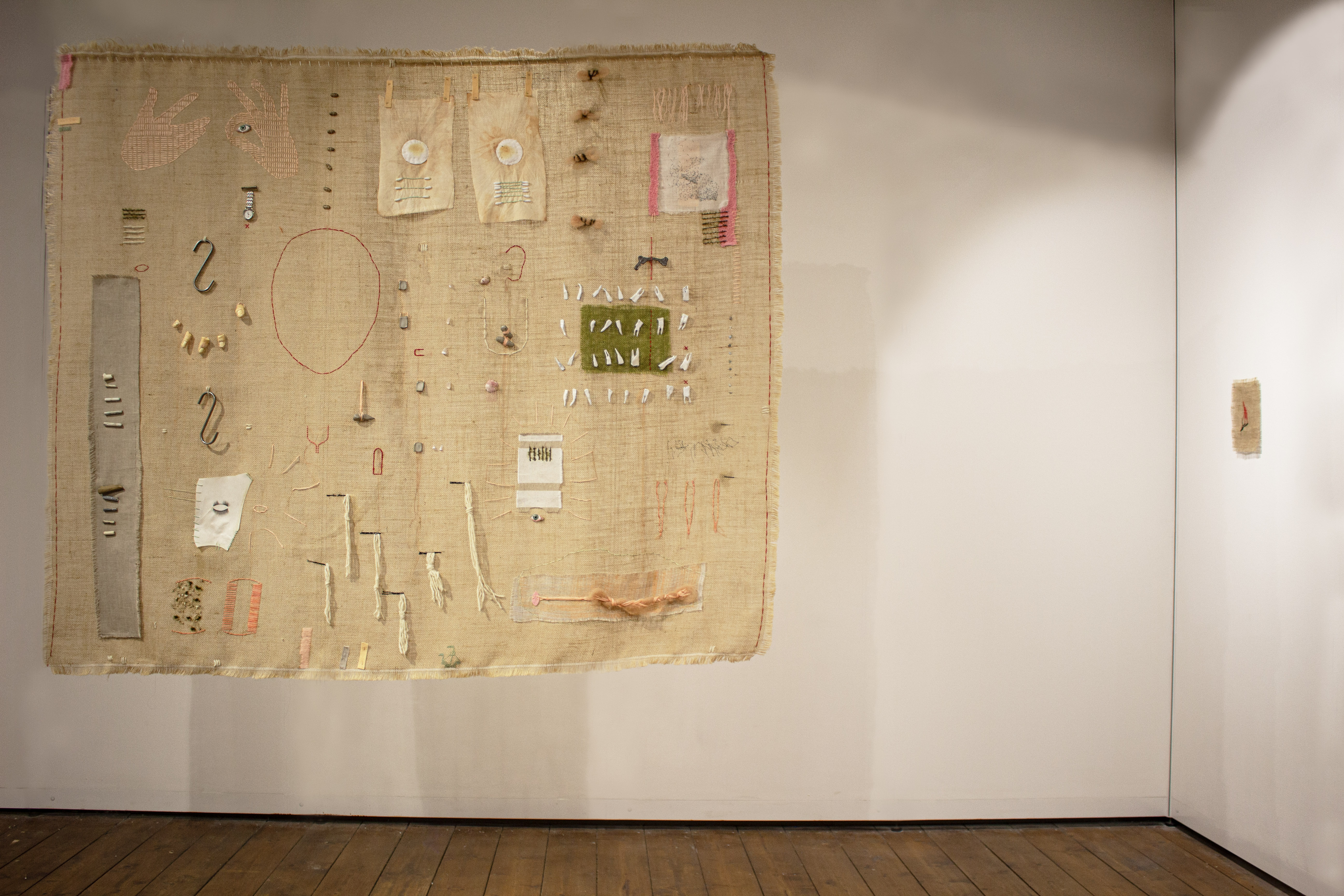

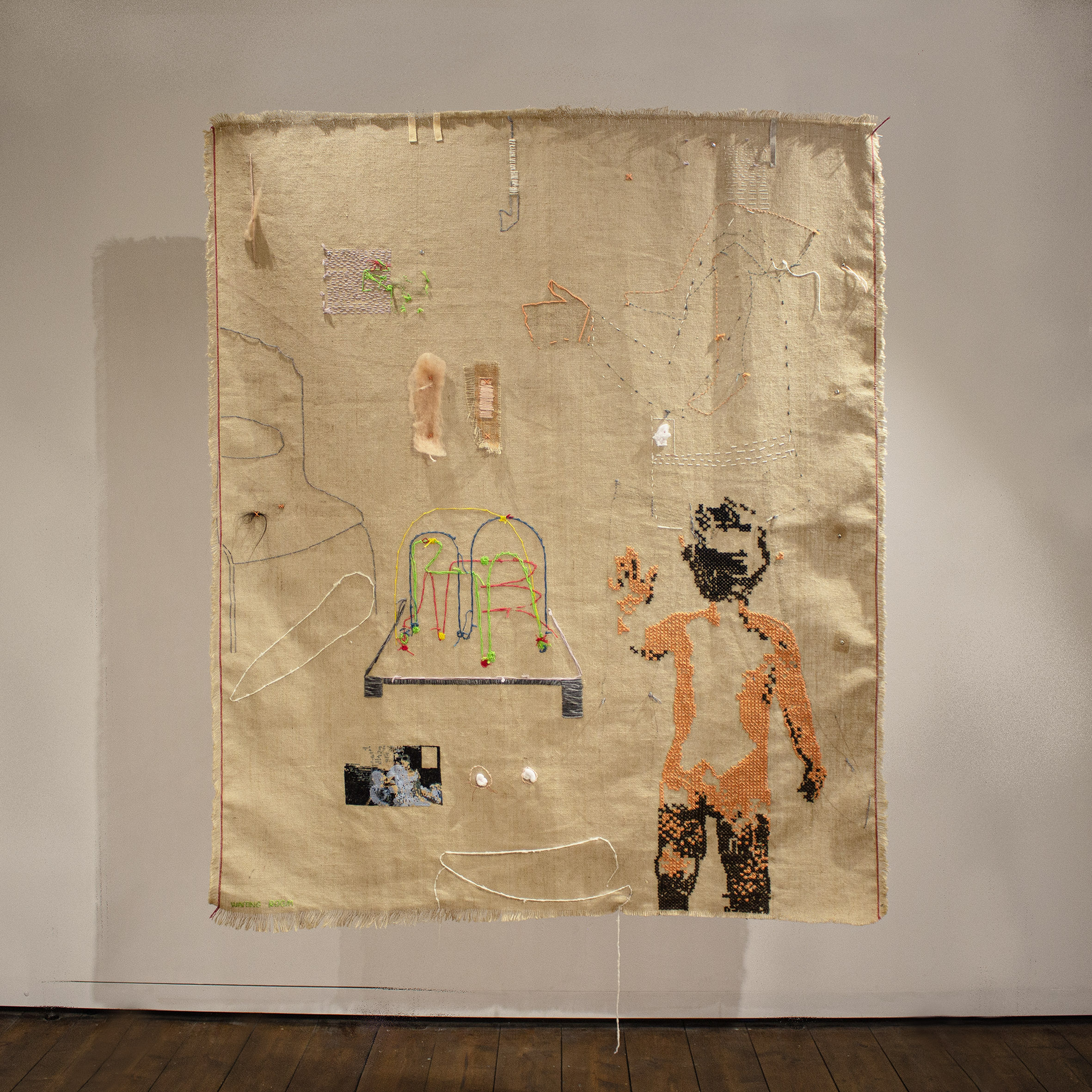

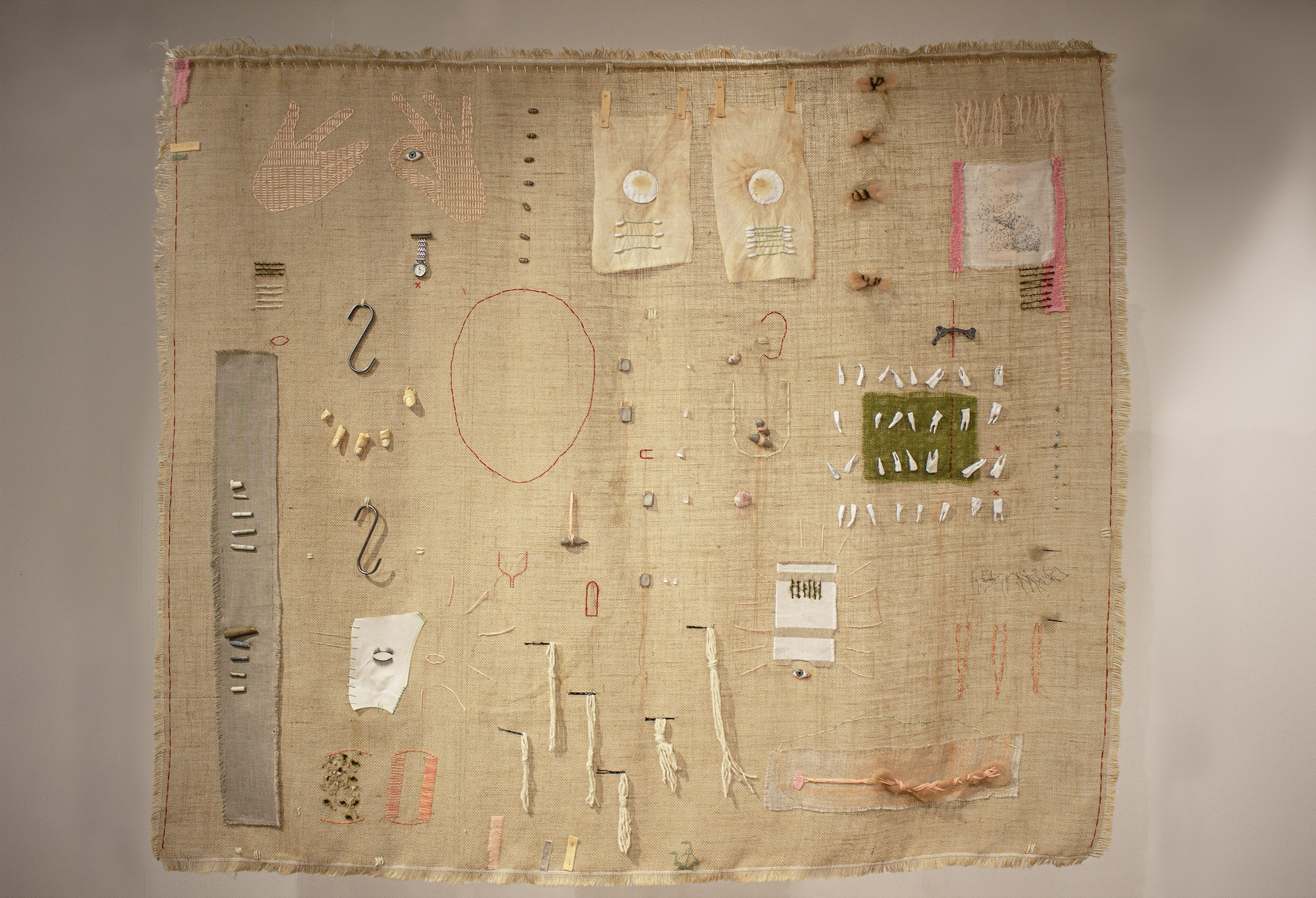

Fabrications is about acts of making and making things up. Often taking a childhood photo as a starting point, Becky Brewis handmakes large, mixed-media jute embroideries which explore the outer edges of memory – where fact becomes fantasy, and the personal becomes mythic.

Jute is tough and hard-wearing but also yielding and easily frayed at the edges, making it an expressive medium for exploring memory, physicality and the passage of time.

These five works are presented in the context of the social history galleries at Verdant Works, where human stories are told through the lens of the jute-making process.

Surgery Waiting Room in about 1995

2020

Mixed media

150cm x 180cm

2020

Mixed media

150cm x 180cm

2023

Jute and embroidery silks

12cm x 18cm

Good hair, good teeth, good skin

2019

Mixed media

150cm x 180cm

2019

Mixed media

150cm x 180cm

Legs

2019

Mixed media embroidery

75cm x 150cm

Little Red Riding Hood

2022

Jute and mixed media

150cm(w) x 185cm(h)